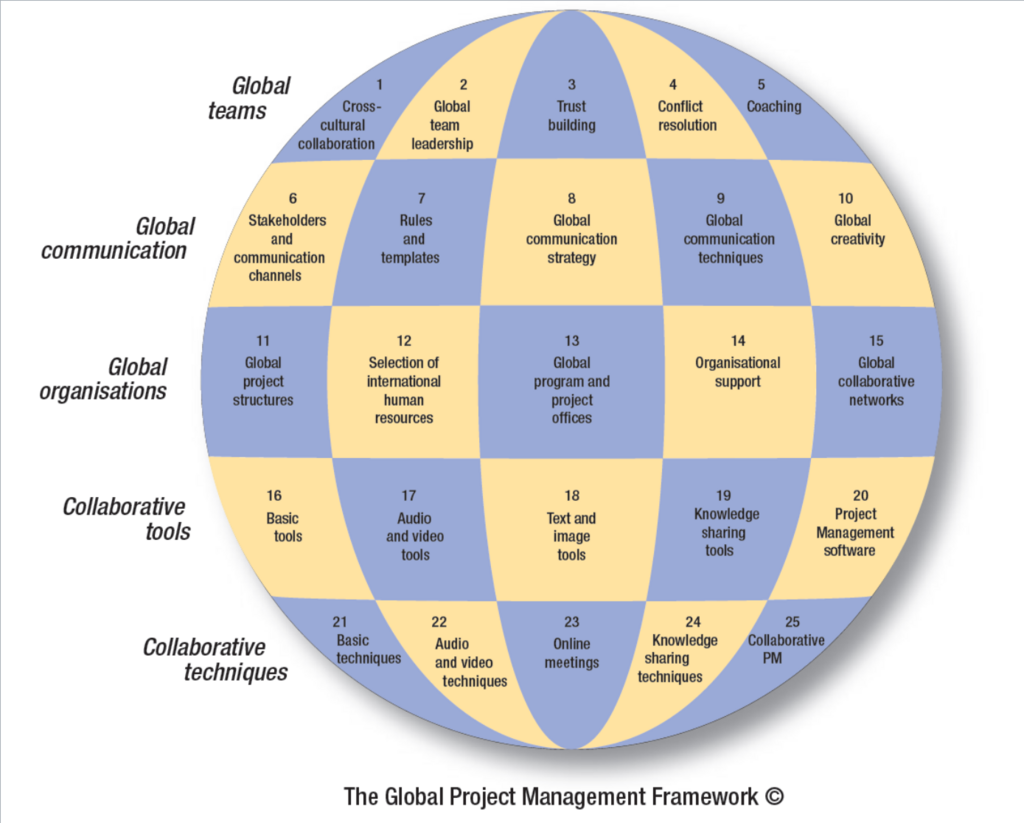

The Global Project Management Framework addresses the combined challenges of the international, distributed and virtual projects, being mainly dedicated to global projects. This novel category can be defined as a combination of virtual and international projects, which includes people from different organizations working in various countries across the globe.

You can use the following dimensions to evaluate the level of complexity of your projects, and identify if you are experiencing the same challenges than other global project managers:

These dimensions can be represented by a radial chart where the centre represents the lower complexity levels: single department, location / time zone, language and cultures. The combination of medium and high marks shows the higher complexity of projects across borders, with team members from different cultures, languages, and organizations working in different nations around the globe: the global projects. Organizations can use the scale above to establish comparisons among different projects, to decide when to apply the best practices, and for risk management.

The project team can be in a single room (project war room), in different rooms and in multiple locations. When all stakeholders are in geographical locations near at hand, face-to-face meetings can be easily organized and the positive influence of body language and social interaction on the efficiency is clear. In global projects, the team members are located at least in two different countries. When the distance among the team members is such that travel is required for physical contacts, the use of phone and videoconferencing becomes essential, requiring the application of communication strategies to ensure a high effectiveness level.

Project team members can work for a single department in one company, for multiple departments, or even for multiple companies. The project managers must adapt their people and leadership skills to the multiple policies, procedures and organizational cultures. The complexity of commercial and contractual processes is also increased, although outside the current scope of the Global Project Management Framework.

Beyond organizational culture, the customs and traditions of different nations and regions can bring more diversity to the work environment, reducing the group thinking and improving the collective creativity. Motivation is often increased, as many people prefer to work in cross-cultural environments because of the rich information exchange. Nevertheless, this diversity can sometimes be the source of conflicts and misunderstandings, and project managers must apply some basic rules and practices to take advantage of the cross-cultural communication, and to avoid its pitfalls.

International companies usually establish a common language for the exchange of information, although the way people communicate is highly dependent on their own native language. For example, if the common language is English, the effectiveness of communication by most non-English speakers will be limited by their knowledge of English expressions, vocabulary and often by their ability to make analogies and tell stories or understand jokes. On the other hand, native English speakers would need to limit their vocabulary to clear sentences and essential words, and carefully confirm the understanding of their ideas by foreign colleagues. The use of online meetings and visual communication are examples of practices discussed in the Global Project Management Framework that can be adopted by project managers to avoid misunderstandings and obtain a high commitment level from all stakeholders, independently of their native language.

The whole project team can be based in the same location, or in different locations in the same time zone. In the other extreme there are project teams with members in completely different time zones, being difficult (or impossible) to organize meetings in common office hours. The effect is twofold. Program and project managers can bring the different working times into their advantages, by creating a “follow-the-sun” implementation, reducing the duration of sequential tasks by a half or a third of the time. The procedures and communication rules must be perfectly defined among people in “complementary” time zones (when there is low overlapping of working hours). On the other hand, important delays can happen, if the exchange of simple information can sometimes wait for a week to be completed, instead of a single day. Global organizations can implement standard communication rules and templates across locations to reduce the possibility of these problems to happen.